China’s latest crackdown on data transfer has sent ripples through the global research community, sparking concerns that the new rules are creating a barrier for international scientific collaborations. Fear of being cut off from key data resources has left some researchers deciding against projects related to China or its populace.

A subtle shift in the landscape of collaboration

A series of regulatory changes, gradually implemented since 2021, has started to reshape the flow of academic and health data from China. These rules range from cybersecurity evaluations of personal and genetic information exported, to restrictions on sharing biotechnology expertise such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology, synthetic biology, and crop breeding knowledge. Even a possible cap on the volume of human genetic data sent abroad is under consideration. The sociologist Joy Zhang from the University of Kent, UK, observes a clear shift in China’s approach to scientific collaborations with foreign entities.

Privacy at the helm

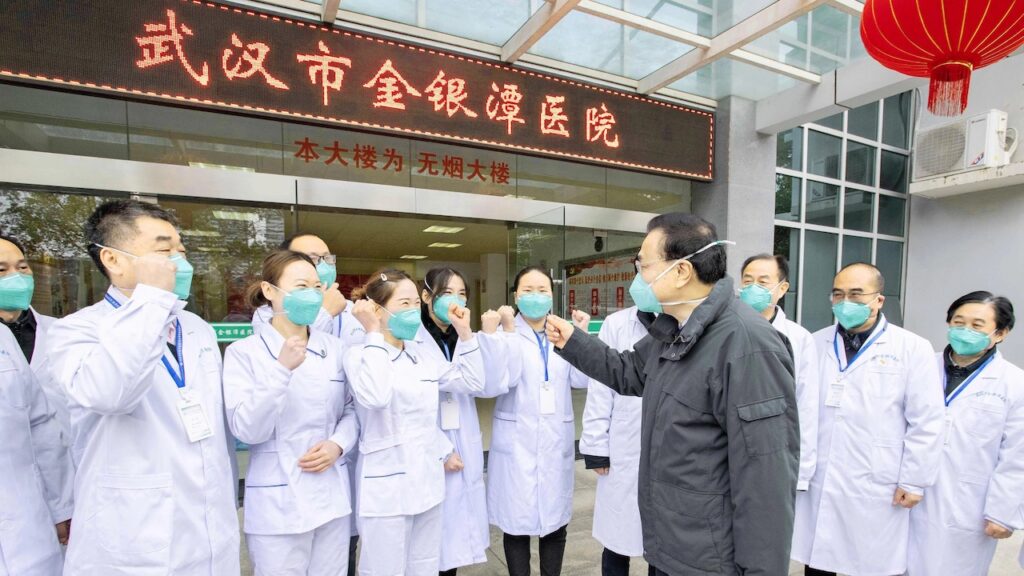

November 2021 marked the inception of China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), designed to prevent the misuse of customer’s personal data by companies or other entities gathering such information. This law mirrors the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) to some extent. Zhang sees these privacy protections as a critical progression for China, given that many Chinese hospitals still lack a robust cybersecurity infrastructure to prevent patient data breaches.

Guarding the data gateway

Further restrictions surfaced in September last year. Now, any organization aiming to transfer personal data, including customer details or information on clinical-trial participants, outside mainland China must undergo a data-export security assessment conducted by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC).

Ziwen Tan, a lawyer at the China Securities Regulatory Commission in Beijing, believes that these assessments offer practical guidelines for managing exported medical and health data, fostering international medical research cooperation. However, Zhang raises concerns about the implications for international researchers needing access to data or collaborators in China.

Impact on the knowledge platform

These new regulations have significantly impacted China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), the largest academic database in China. Following the new rules on data export, CNKI suspended foreign access to certain parts of its database, which has left international researchers in a lurch. The suspension has deprived researchers of crucial data resources, further hampering their understanding of developments within China.

The plight of clinical research

The future repercussions of the data-export requirements on clinical research in China remain uncertain. Unlike GDPR, PIPL doesn’t currently have exemptions for sharing data among researchers. This has left researchers in life sciences, like Zhang, anxious about the draft restrictions on the export of human genetic data.

National treasures under scrutiny

China’s data regulations have now extended to surveillance of technologies regarded as nationally significant. This includes proposed limitations on the export of certain advancements, such as CRISPR gene editing and synthetic biology.

A chill in the air

These tightening regulations reflect the growing digital divide between China and Western countries, according to Ben Hillman, a political scientist at the Australian National University in Canberra. He sees these restrictions as part of a broader censorship program aiming to obstruct critical analysis of China’s public policy and politics by foreigners. Zhang notes that the new regulations are causing Chinese researchers to reconsider sharing data with their foreign counterparts, further impeding open discussion in international forums.

As we navigate these uncertain waters, we invite our readers to share their thoughts. What’s your perspective on these developments? Do share your insights in the comments below.